Ghosts express the meaning of the sites they haunt.

A ghost may begin its journey as a kind of rumor. The social process by which this rumor fuses with local circumstances is complicated, but knowable. Artists, children playing at recess, historians, promoters, and countless others channel the social truth of a ghost, helping to attach it to a specific place. In some rare cases, the provenance of a ghost may be traced back to a known medium; in most cases, it emerges from out of our shared ghost-lore, which has evolved over generations. A core principle of historically informed ghost hunting is that to be investigated, a ghost must first be located within a sociocultural neighborhood.

A corollary to this principle is that we share space with ghosts. They haunt crossroads, seaside forts, abandoned homes, and remote hotels—any space whose communal significance is unstable or sunken. They do not occupy these spaces in the normal sense, but abide in them as a kind of potential. Ghosts are difficult to signify because, in part, they seem to exist outside of time in a spiritual stasis while also unfolding in time as a sequence of gestures (a haunting). A ghost is, in this way, like an algorithm or a mathematical function that may be meaningful in use, but whose existence as an independent object is ontologically fraught. The manner in which a ghost abides is a mystery; the character of its haunting is highly site dependent.

The geometry of a specific site, its history and purpose, and the role it plays in the overall ecosystem (the interconnected spaces surrounding it) together define a haunt, the home-world of a ghost. Walls may bound a haunted space, but are not a requirement. A parking lot can be haunted. The circumambulation of spirits does not draw a map or respect parcel lines. Ghosts are drawn to the locus of greatest trauma within the catchment area of their former lives. Some trace a fracture between spaces, others are cast in auratic stillness like church windows.

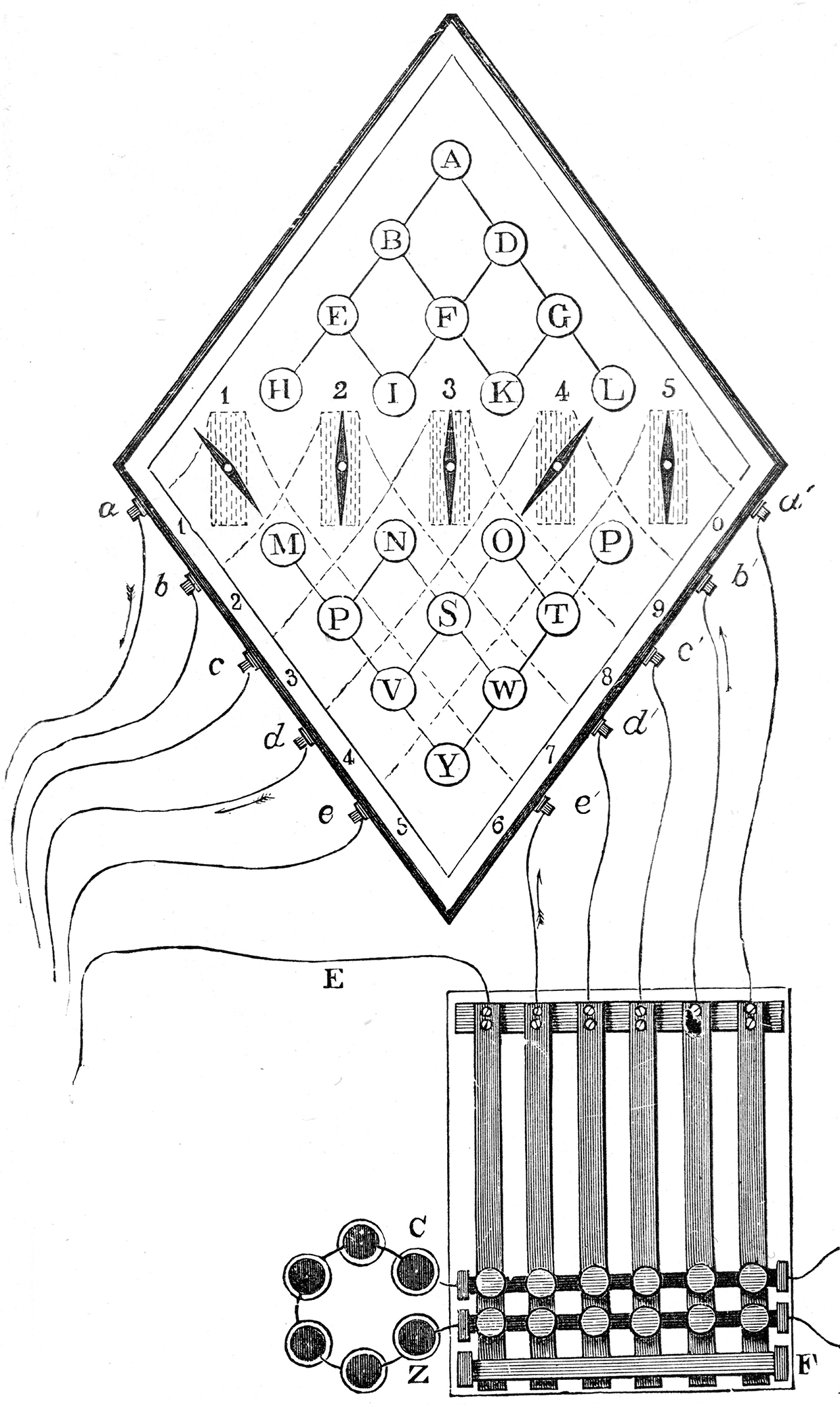

Every investigation begins with a diagnostic survey, an overview of the site and its formal features. Baseline environmental readings are collected in the first stage of the survey: temperature curves, lighting angles, floor-level air currents, whisper saturation, and a host of other details about the structure of the house and its flow lines. This baseline data is supplemented with a functional analysis. Rooms are diverse and serve diverse functions. A gallery, music hall, parlor, foyer, den, bathroom, stage, basement—all serve different needs and invite different kinds of behavior.

The purpose of the diagnostic survey is to understand how the built environment is socially configured. How do we inhabit a space, how might it be haunted? Imagine unlatching a window in a small bedroom on the second floor of an old house. You can hear the chirp of the latch itself, the seal of paint around the frame coming loose, and the near-silent harmonic signature of the room changing; you can feel the air pressure stabilizing between the room and stairwell outside of it as the hum of a distant generator builds. Whatever else you hear or feel, beyond what is intuitively assignable to material causes, is worthy of special attention.